Andy Warhol was born in 1928 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania—steel town, coal dust, the clank and clang of a crumbling industrial America. His parents were immigrants of Rusyn descent, devout Byzantine Catholics who arrived with little and clung tightly to what they had. His father, a coal miner, worked beneath the ground while his mother, a homemaker with hands always busy—either stitching paper flowers or humming liturgical hymns—nurtured the home above it.

As a child, Warhol contracted Sydenham chorea, a neurological illness that left him bedridden for long stretches. But it was in this isolation, in the dim light of their modest apartment, surrounded by stacks of movie magazines and hand-me-down newsprint, that his imagination took root. Faces—Hollywood faces, manufactured and eternal—became his obsession. He drew constantly, copied endlessly, clipped and archived like a boy already preparing to become his own museum.

From the very beginning, Warhol’s gaze was fixed upward—not in worship, but in inquiry. He wasn’t infatuated with the wealthy or the beautiful; he wanted to understand how they worked. Fame, fortune, and flawless skin weren’t just dreams—they were systems. And Warhol, a sickly kid from the working class, would crack the code. Not to be part of it. To remake it.

After graduating from Carnegie Institute of Technology in the early 1950s, Warhol moved to New York and started out as a commercial illustrator. His linework—fluid, effeminate, seductive—quickly won over Madison Avenue. But Warhol’s ambitions were never just to serve the market; he wanted to deconstruct it. He had grown up inhaling pop culture, but now, he was going to exhale something stranger, flatter, shinier: Pop Art.

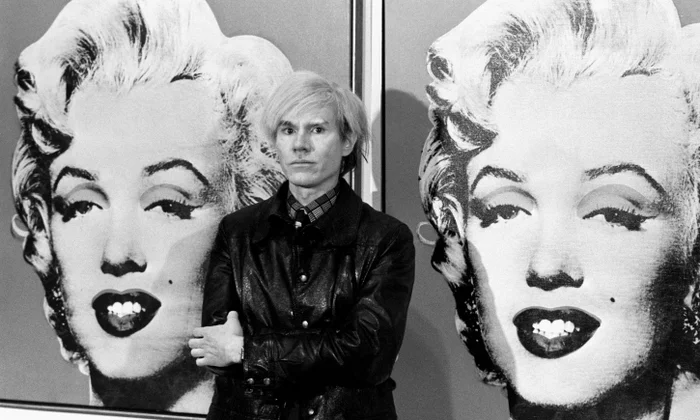

By the 1960s, he was producing canvases of Campbell’s soup cans, Coca-Cola bottles, and endlessly repeated portraits of Marilyn Monroe. They were not endorsements. Nor were they satires. They were observations, cool and methodical, of a society that consumed identity the same way it consumed canned goods. His art wasn’t about meaning—it was about looking. In Warhol’s world, perception eclipsed purpose.

A can of soup was never just soup. “In America,” he once said, “the richest and the poorest all drink the same Coke.” It wasn’t a utopian vision, and it wasn’t quite cynical either. It was the neutral, brilliant nihilism of advertising, reappropriated as fine art. Warhol offered no answers—he just showed you what was already on the shelf.

By the late ’60s, Warhol was no longer merely an artist; he was a brand, a phenomenon. And then, in 1968, everything changed. He was shot at close range by Valerie Solanas, a fringe writer and radical feminist. The bullet tore through his chest and nearly killed him. Warhol survived, but something in him calcified. The Factory, once a bacchanalian playground of drag queens, dancers, and speed freaks, grew quieter. His work became more commercial, more controlled. Gone were the experimental films and conceptual provocations. In their place came commissioned portraits—for heiresses, oil magnates, politicians. The critic might say he sold out. Warhol might’ve said he was just selling what people were already buying.

Still, it was during this ostensibly tamer phase that he created some of his most political work—though not in the way politics likes to be talked about. In 1972, in the heat of the presidential campaign, Warhol designed a searing portrait of Richard Nixon painted in acidic greens and flaming reds, captioned with a blunt directive: Vote McGovern. He wasn’t writing op-eds or delivering speeches—he was waging war with pigment and print.

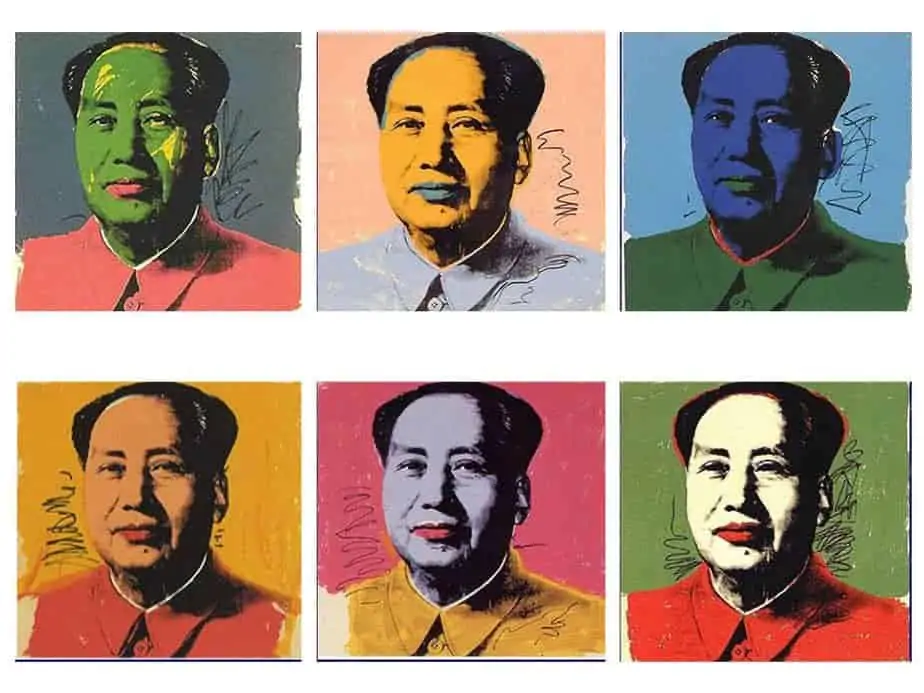

Soon came portraits of JFK and Jackie, Jimmy Carter, even Mao Zedong. The Mao series, in particular, was a masterstroke: 199 garish renderings of the Chinese leader in saturated technicolor, equal parts propaganda and product. Mao wasn’t just a revolutionary; in Warhol’s hands, he became a brand. The line between icon and commodity blurred, then disappeared. Why shouldn’t a dictator be rendered as reproducible as a soap commercial?

Toward the end of his life, Warhol turned inward, if not emotionally, then archivally. He began assembling hundreds of “Time Capsules”—cardboard boxes filled with the detritus of his daily life: newspaper clippings, unpaid bills, grocery receipts, party invitations, lunch leftovers. It was memory as material, as clutter, as content. Warhol was documenting not what mattered, but what existed—without filter, without hierarchy.

He died in 1987, at the age of 58, from complications following routine surgery. It was an oddly unceremonious end for a man who had spent decades elevating the ordinary to the spectacular. But in some ways, it suited him. Warhol, after all, believed in the surface. “I am a deeply superficial person,” he once said. And yet, if you stared long enough into that surface—into the gloss and the glitter and the flat, fluorescent glow—you found something else.

Not emptiness.

But the echo of a society trying desperately to believe in its own reflection.